Essay by Marianna Rosen

December 27, 2021

Marianna Rosen is the editor of Fine Art Globe. Born in Moscow, she is a writer, TV producer, and journalist whose work has appeared in the Observer and Elle. She holds a master's degree in international affairs from Columbia University and is pursuing a PhD.

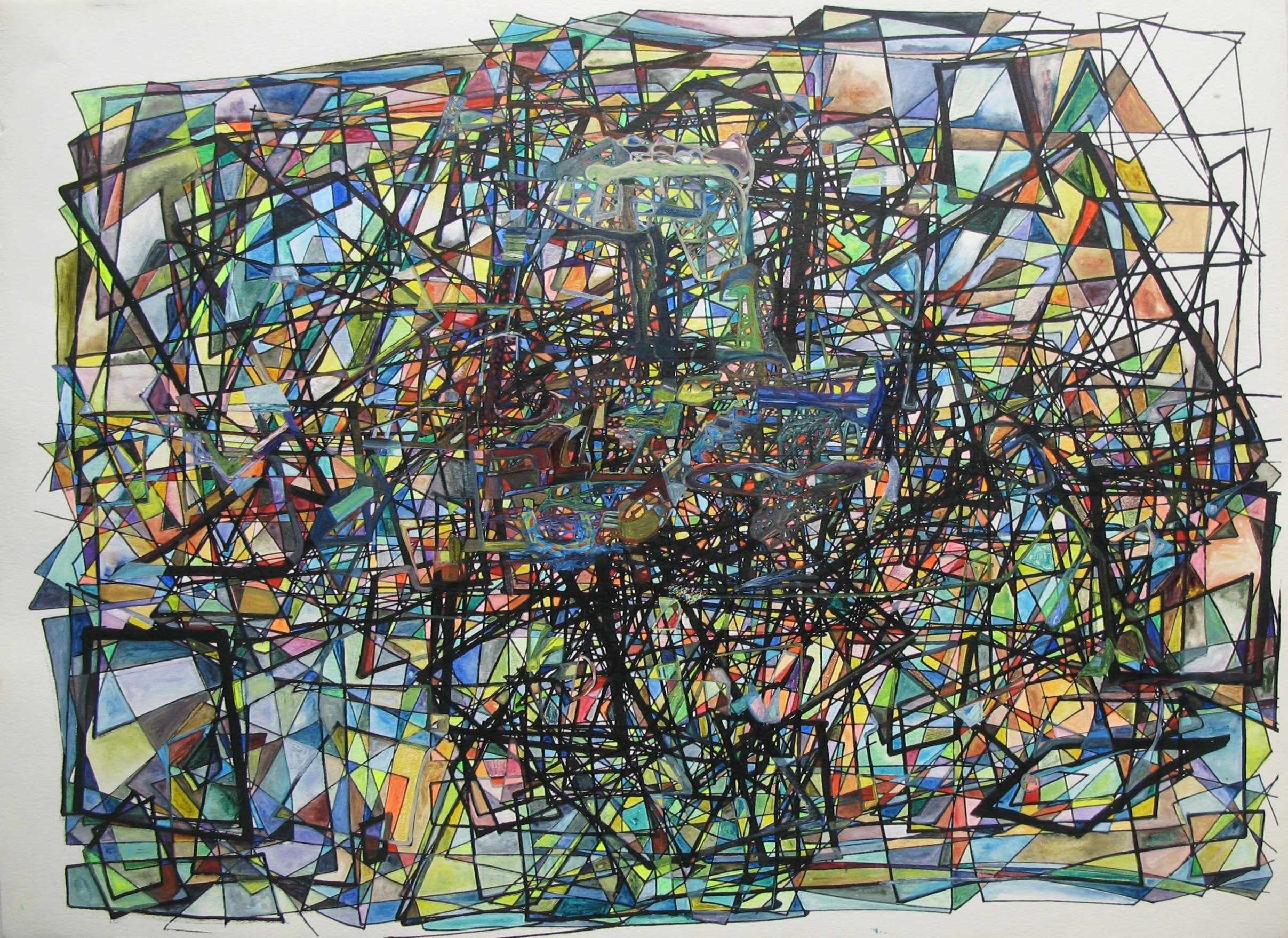

Jacqueline Frankel. Untangle. (2021). Watercolor mixed media on paper. 43 x 42 inches

Read the article here or below

Jacqueline Frankel: Letting Artwork Breathe

Brooklyn-based artist reinterprets the human body and its invisible cadences within an abstract oeuvre

By Marianna Rosen

Jacqueline Frankel, Bust. (2019). Watercolor, mixed media on paper. 32×42 in. (Courtesy: Jacqueline Frankel).

Georgia O’Keeffe once said that with colors and shapes, she could say things that she could not with words. The ambition to transmit the incorporeal by way of material properties of painting eventually became abstract art’s problem—the drive “to abolish the form” turned painting’s texture, line, color, and brushstroke into its subject. But the strive to communicate the inner processes of human experiences remained. Insofar as it inhabits a level that is beyond content, abstract art is akin to music.

Jacqueline Frankel, Soundless Shapes. (2021). Mixed-media on paper, 43×32 in. (Courtesy: Jacqueline Frankel).

One wants to compare Jacqueline Frankel’s artwork to jazz—the unifying feature is the intuitive, improvised process and its corollary autoreferentiality. An encounter with her work is an exercise in feeling, a vortex of it to be sure; being immersed in it is to enter that vortex, first, on the picture plane by following the twists of the brushstroke or the pencil line, then, almost meditatively, on the emotional one. Spatial forces map the complex sentient landscape; the linework exerts centripetal force, pulling the viewer inward.

Jacqueline Frankel, Sparkle in the Eye. (2019). Mixed media watercolor on paper, 22.5×31 in. (Photo: John Sluder).

Multiplicity is a distinctive feature of her linework—the starting point is indistinguishable, one strain leads to another, the lines swell and twirl, enfolding into a biomorphic whirlpool—an emotional expression that is not defined or, for that matter, ever finished.

Jacqueline Frankel, Left to Right—With Neutral Overall. (2021). Mixed media on paper, 42×32 in. (Courtesy: Jacqueline Frankel).

This multiplicity is most manifested in Frankel’s “Recent Highlights” series of mixed media on paper. A skein of layered strands of luminous color that refuse to be compressed into a distinctive shape affects a sense of effervescence. It appears to be suspended over the picture plane — its flatness abolished. A sculptural, thing-in-themself presence. The artwork becomes an object giving the viewer a sensation of shared space. Paradoxically, this “object” state brings an aura of vulnerability that comes with visceral, bodily experiences. Perhaps, this is how the human body is revealed in a work of abstract art.

Jacqueline Frankel, Study in Purple. (2017). Watercolor on paper, 18×24 in. (Photo: John Sluder).

The artist says that she aims not to represent but to discover. Indeed, like love, art has been said to invite one to discover oneself. Jacqueline Frankel sees her practice informed by a desire to establish a connection between the image and the inner emotional realm, to capture an emotional fabric of a human body in time and space—if one imagines space and time imbued with emotion. “Every painter paints herself,” as Renaissance maxim ran — you bet, except the ‘self-ness’ is transferable. Once there is a viewer, it transforms into a reflection of a viewer’s mind— the ever-changing interaction between the viewer and the artwork. And this is one reason why the work of art is never finished.

But it is also Frankel’s intention—she says that she finds, “the most delight in the sense of unfinished work,” its compositional and chromatic open-ended-ness that precludes the shapes to reveal themselves, letting, as she says, “the work breathe.” Indeed, the artist’s linework has a rhythmic quality to it, as if reproducing invisible respiratory rate.

Jacqueline Frankel, Changeover. (2012). Screen-printing and acrylic paint, 30 x 22.5 in. (Courtesy: Jacqueline Frankel).

Frankel’s process is initiated with control and deliberation. Yet, the linework indicates an absence of choice—a space of artistic sanctum sanctorum, where accident and surprise are possible, the outcome undetermined.

Her artwork is also a part of and a reflection on the environment of the place she now calls home. Born and raised near Basel, Switzerland, Jacqueline Frankel moved to New York City in 1993 after studying painting at Basel’s School of Art and Design. New York’s cultural, emotional, and intellectual vibrancy became part of her life-long artistic practice. Frankel—an artist, a mother, a wife, and an educator — the agony of prioritizing these in a sentence evinces the delicate balancing act existing throughout our lives and careers—breaks her practice into two main periods: before and after her son was born, the time in between mainly devoted to raising him and working as an art educator.

Jacqueline Frankel, Closing the Loop. (2000). Mixed media on canvas, 58 x 64 in. (Courtesy: Jacqueline Frankel).

The artist’s output comprises wide variety of mixed media techniques, including acrylic, oils, screen printing, ink, graphite, markers, pastels, and watercolor — a continuous search for hidden structures, patterns, and colors. Recently, it has been watercolor that she prefers the most— for its sensuousness and transparence that she finds enthralling.

Jacqueline Frankel, Trifold. (2021). Mixed-media on paper, 42×32 in. (Courtesy: Jacqueline Frankel).

The experience of looking at Frankel’s art brings to forefront the seemingly irreconcilable: the mastery of her brush- and linework, the draftsmanship, the emotional depth and pictorial density of her painting with the absence of a solo art show. Her explanation is that she has not felt compelled to have her work shown. “I perceive all of my work as an ongoing project, an interconnected whole. So, I’ve always been reluctant to separate the works,” Frankel told me during our recent conversation. And now, with a show in the works (stay tuned for more information), not much has changed in the artist’s practice, for it was not the desire for recognition and membership in the art world that was driving it all these years but actual belonging, reached through that inescapable and daily need to engage, to create, and to discover.